Welcome to “Decisions in board games”, a three-part series on engaging players through meaningful decisions in competitive multiplayer games. In this post we will discuss why decisions are important and the basic outline of how to reason about the decisions in your games. The second post will be a deeper dive into what really makes decisions “meaningful”. The third and final post will share a number of examples from Legends of the Arena and how we applied board game decision theory to create a more engaging experience for players.

Decisions are central to board games

There are numerous definitions of what a board game is, but many of them include decision-making as a core element. Decisions help to separate games from other activities like reading a book or watching a movie - they give players agency which is essential for engaging gameplay. Across repeated plays players can try out different decisions and learn from their mistakes. There are other avenues to achieve agency - sports and digital games often rely on physical skills. However, board games largely eschew these mechanisms (outside of dexterity games).

Therefore, it is very likely that any game you play or design will require players to make some decisions. What decisions make games better? Can a game offer too many decisions? Too few?

Approaching decisions as a designer

When designing a game, the first decisions you should identify are those that are key to the experience you want your players to have. These are the decisions that are core to how players view your game. In Legends of the Arena, we wanted combat to be at the core of the game, so decisions center around what your fighter is trying to do - counterattack, shoot a fireball, block incoming attacks, coordinate with an ally, etc.

There are many other decisions that are going to arise naturally from your game mechanics - desirable or not. For example, many games have limits on hand size. Players must decide which cards to discard when they reach the maximum number of cards in their hand. These secondary decisions reflect the inherent structure and limitations of your game; while certain players will doubtlessly find them interesting they don’t serve the core experience your game is aiming for.

Once you’ve identified the decisions at the heart of your game - as well as those on the periphery - you need to assess whether they are working as intended.

Variety

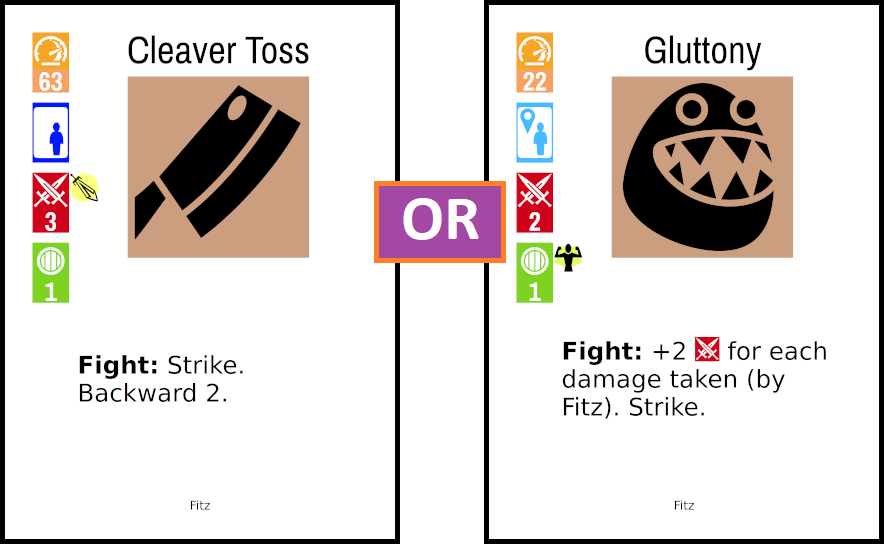

Decision variety can refer to having different options or new context for familiar options. 4X games like Scythe give players a choice between options such as exploring new territory, attacking opponents, or creating buildings. Within each of these areas there are additional options - which opponent to attack, which building to build, etc. In Legends of the Arena and other tactical dueling games, variety is often driven by the arrangement of combatants on the board; if your opponent is adjacent to your fighter, you are likely going to select between different melee attacks, but if the opponent is far away you will probably weigh different ranged attacks.

It is important to have a variety of decisions in your game to keep players engaged. Fortunately this is quite easy to achieve for most games - keep your core experience in mind and seed the game with decisions that make players feel like they are masters of a space empire, epic gladiators, or even migrating birds.

Volume

Through play testing you should immediately get a feeling for whether your game has too many or too few decisions given the weight and duration you are targeting. Note that it isn’t just the number of decisions that matters, but also how long it takes to make them. Think of volume as “total amount of time spent making decisions”. Watch for other players losing interest as the active player hunkers down to figure out the right path forward. Focus on the worst case scenario - even if only one player seems to be struggling to move the game forward in a reasonable timeframe, that is a warning sign that there are deeper issues (perhaps everyone else is just being polite and trying to move things along by deciding randomly).

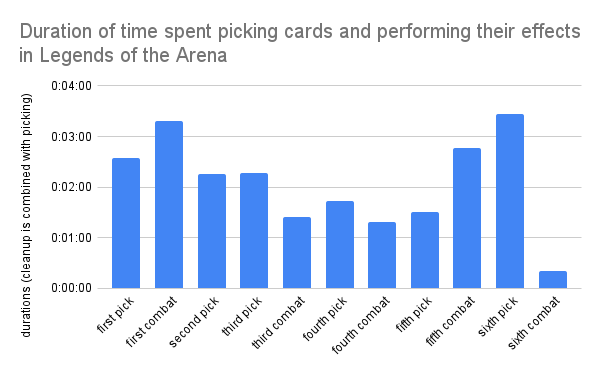

Once you’ve done a few rough passes you can fine-tune your search for overly time-consuming decisions. For Legends of the Arena, we played via Tabletop Simulator and recorded our sessions using screen capture software. Then we walked back through the recordings, noting each decision and how long it took to make that decision. We removed decisions that took a long time to make but weren’t core to the game experience.

Analysis paralysis

On the surface, increasing the volume of decisions in your game may feel like an easy way to achieve design goals: more decisions means more replay potential, a more authentic simulation, and greater variety of decisions. But there is a catch - games that inundate players with too many decisions (or a smaller number of extremely weighty decisions) risk sending players into analysis paralysis. In this state, players spend inordinate amounts of time trying to compute future possible outcomes rather than making a decision based on intuition, role playing, or strategy. The game grinds to a halt and players become disengaged.

Some players will always be more prone to analysis-paralysis, but your game should also be careful not to encourage this style of play. Consider adding some amount of uncertainty (randomness, hidden information, etc. - the next post in this series discusses uncertainty in greater detail). Uncertainty adds a layer of “plausible deniability” that can thwart excessive analysis; if not all factors are known then even the most carefully laid plan can fail. By reducing the return on investment for excessive analysis, your game can encourage players to focus their attention elsewhere. Keep publicly visible information minimal and easily summarized; serious players will attempt to analyze all of this information to make informed choices.

Meaning

Volume and variety are a good starting point, but the best board games go further and deliver meaningful decisions. The word “meaningful” is doing a lot of work here, so let’s unpack that a bit. Per Brice Morrison there are four elements to meaningful choices:

- Awareness - The player must be somewhat aware they are making a choice (perceive options)

- Gameplay Consequences – The choice must have consequences that are both gameplay and aesthetically oriented

- Reminders – The player must be reminded of the choice they made after they made it

- Permanence - The player cannot go back and undo their choice after exploring the consequences

For board games we can interpret these general tenants more narrowly. Awareness and permanence are typically available by default in board games. Players are interacting with a limited set of physical components; the set of options is laid bare, and, unless the other players are feeling exceptionally charitable, there usually is no undo mechanism.

Reminders are also easy to come by in board games. These can take many forms - a tableau of cards in front of a player, new cards added to a deck, or pieces added/removed from a board.

That leaves consequences. Aesthetics in board game mechanic terms can be thought of as “thematically relevant”. In an investing game, a player who invests in stocks should have greater variance on returns than a player who invests in bonds - even if the expected value of return is the same in both cases. Ultimately gameplay consequences are typically where board games stumble and fail to implement meaningful decisions. There are three main failure modes - calculations, dominant strategies, and decision memory.

Calculations

In the worst case, a decision is really just a calculation. A player simply needs to compute the value of a few options and select the best one. As a designer, you should expect that making this harder to calculate will simply increase how long it takes people to make decisions - eventually leading to excessive decision volume or analysis-paralysis. Some calculations can actually be performed ahead of time, e.g. openings in chess. This rewards players with good memories, but unless your game is meant as a test of the ability to recall information your players will be better served by offering a variety of decisions that cannot be easily pre-computed.

Dominant strategies

Even if the calculations performed by players don’t reveal a straightforward best option, players may end up with an understanding of the probability of success given each choice. When a certain option leads to victory a large percentage of the time - even if it isn’t gauranteed - the game is considered to have a dominanat strategy. Players may still choose not to pursue the dominant strategy, but this is often due to a desire to try something new, rather than a true decision based on the merits of the game itself. Decisions lose meaning when the outcome is well understood.

Decision memory

On the first turn of a deckbuilding game, a player can often choose between many cards to add to their deck. As the game proceeds, the number of options decreases - not because there are fewer cards to choose between, but because the cards that player previously added to their deck only synergize with a subset of the available cards (many of the available cards can be eliminated from consideration with straightforward calculation). This isn’t necessary a bad thing, but designers must be careful not to assume that two decisions with the same options are equally meaningful. Once a player has started down a certain path or picked a strategy, many of their remaining decisions may be “on-rails”. Consider giving opportunities for players to bail out of their chosen strategy or offer different paths within the same general strategy.

Real time elements

One trick to achieve meaningful decisions even when the ultimate decision is just a calculation is to introduce a real-time element. Sports and digital games (and some board games) incorporate real-time elements to turn straightforward calculations into moments of true player agency - because the player must have the requisite skills to make the right decision quickly. Many board game tournaments introduce time limits to achieve the same; in competitive chess, clock management is extremely important. Commentators assess the accuracy of each move (how close the player got to the correct move), and the best players spend their limited time wisely to save their focus for key turns. Some games go further and incorporate real-time elements directly into the game (see Space Alert or Captain Sonar).

For most board game designs, adding real time elements is at least somewhat controversial. Players often choose board games for a less frenetic experience, and they enjoy the opportunity for thoughtful contemplation. Real-time games are considered their own sub-genre and they do not comprise a large portion of the market.

So what is a board game designer to do? In the next installment we will dive in further and offer some strategies designers can employ to offer meaningful decisions.

Conclusion

We’ve discussed why decisions are crucial to board game design and how you can begin to reason about the decisions players will make in your games. In the next post we will talk about valuation, reading, and uncertainty - and how these elements determine the decision space and ultimately conspire to create true player agency through meaningful choices.